Competing with Silicon Valley for engineers, aerospace firms start recruitment in pre-kindergarten

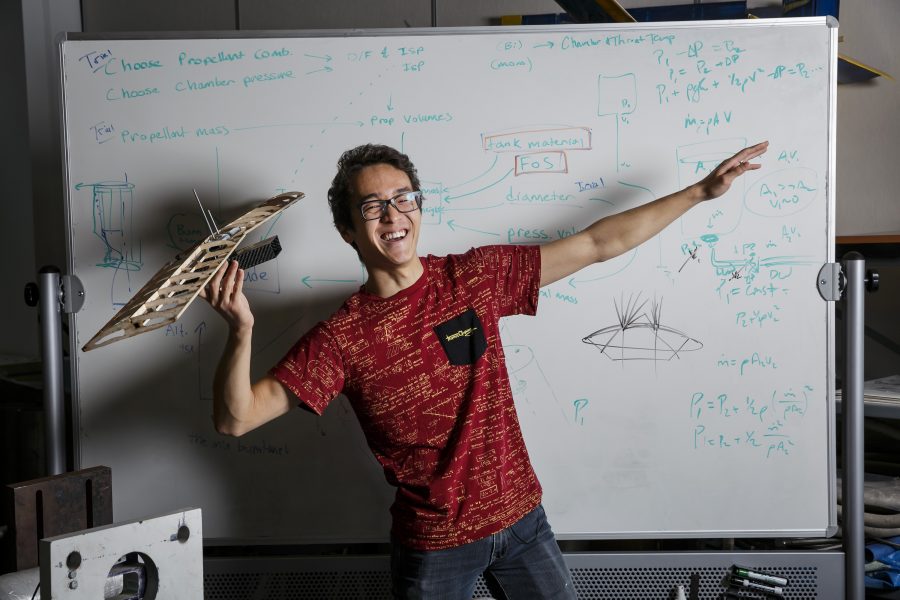

Timothy John, 25, an aerospace engineering senior at UCLA who hopes to go into the defense industry, poses on Jan. 4, 2017 at a Design Build Fly’s club lab at UCLA in Los Angeles, Calif. (Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

January 12, 2017

By Samantha Masunaga

LOS ANGELES — USC mechanical engineering junior Stephanie Balais developed a passion for aerospace after joining the university’s AeroDesign team and helping to construct an airplane fuselage hours before transporting the plane to a competition in Kansas.

As internships beckoned, she sent in a number of applications to top defense and aerospace firms. But Microsoft Corp. snagged her first. This summer, Balais, 20, will spend 13 weeks in Redmond, Wash., working in the tech giant’s manufacturing and supply chain department.

Silicon Valley and other tech centers have always been popular landing places for young engineers, with their lure of cutting-edge technology and top-notch pay. But aerospace companies are facing an even stiffer challenge as web and computer companies, and other sectors like the auto industry, move into areas like drones and autonomous systems.

Aerospace employers are realizing they have to dig deeper — and adjust their messaging — to capture top tech talent.

They are starting to reach out earlier to potential employees — as early as elementary school or even pre-kindergarten — to get them interested in science and math. And they’re recognizing the challenge they have building awareness with a generation that never had a real space race, but grew up with Google, Snapchat and Apple as part of their daily lives.

“This is something that’s very critical to our member companies,” said Dan Stohr, spokesman for the Aerospace Industries Association trade group. “They’re putting serious money into this, to the tune of millions of dollars a year.”

Lockheed Martin Corp. has launched a program called Generation Beyond aimed at encouraging middle school students’ interest in deep space exploration. The initiative includes a class curriculum, a downloadable Mars weather app and a traveling school bus modified so that children riding it can see the Martian landscape through the windows.

“One of the things we’ve been seeing is that this generation of students doesn’t necessarily know or have grown up with Lockheed Martin, as their parents did,” said Steve Hatch, the company’s director for central talent acquisition, of current college students. “As we look at the competition, how do we go attract that talent sooner … but at the same time, get them interested in STEM.”

In early 2015, Northrop Grumman Corp. opened an innovation center called NG Next based in Redondo Beach, Calif., where it is doubling down on basic research to figure out solutions to problems that may be years in the future. The organization takes a more aggressive approach to experimentation, which can be attractive to potential employees looking for a creative work environment.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 26,000 aerospace engineers were employed as of May 2015 in product and parts manufacturing, a category that covers about 70 percent of the aerospace and defense industry, but excludes many suppliers in sectors like shipbuilding. Joining them were about 5,900 electrical engineers, about 14,000 mechanical engineers and 12,000 software developers of systems software.

In computer and electronic product manufacturing, there were about 5,700 aerospace engineers, 30,300 electrical engineers, 18,400 mechanical engineers and 48,600 software developers of systems software.

Defense firms have long maintained a presence on college campuses, whether at career fairs, sponsoring student engineering competitions, serving on deans’ or department advisory boards or providing scholarships.

“Students encounter Google and Amazon frequently on the web,” said Jayathi Murthy, dean of UCLA’s Engineering School. “So in order for (defense companies) to be heard above that, they really need to engage with us on campus, and they do.”

A meeting with a Northrop Grumman executive during a USC recruiting event piqued Justin Jameson’s interest in working at the company. It ended up being the only place he applied to after graduating from USC in 2009. Jameson, 29, has now worked at Northrop Grumman for more than seven years.

“I looked at a lot of the big consulting companies as well, but at Northrop Grumman, they offered me the chance to come in and work on real problems,” he said. “At a consulting company, I would be solving someone else’s problems.”

Defense firms emphasize a mission of national security with recruits, said Robin Thurman, director of workforce policy at the Aerospace Industries Association. And the unique, real-world nature of the work gives it a “cool” factor for some students.

“In the internet world, they’re going to work on advertising algorithms … big data analysis, which can be fun and exciting and interesting,” said Chris Hernandez, vice president of NG Next. “But I’d like to compare my airplanes and spacecraft to that any day of the week.”

That aspect attracted Addison Salzman, 21, who will graduate from USC in May with a degree in aerospace engineering. Salzman, who is interested in higher-level aircraft design, has already landed a full-time job at Boeing Co. and will start in July.

“One of the big reasons that I chose it is because they have their hands in not just defense, but they have a very large commercial airplanes business,” he said. “It gives me a cool opportunity to explore the different applications of aerospace technologies.”

Timothy John, an aerospace engineering student at UCLA, has been interested in space exploration since elementary school and has sent out a number of job applications to defense companies.

John, 25, said he’s looking for longevity and growth in potential employers, but also hopes to work on an airplane or spacecraft.

“I’m pretty indiscriminate,” he said. “Any projects that include planes, like anything with a jet turbine, like a F-16 or F-22 or stealth bombers. Or even missiles.”

Though Northrop Grumman’s NG Next was not established specifically for recruiting, it has become a useful tool in hiring, Hernandez said. New employees can be part of an environment of rapid development and experimentation not generally associated with large defense contractors.

“For us to achieve the great things that we need to achieve to solve the nation’s toughest problems, we have to push hard,” Hernandez said.

The organization’s four main components — basic research, applied technology, advanced design and rapid prototyping — employ about 800 full- or part-time people, though faculty from research universities can also collaborate with NG Next scientists.

The organization was also designed to have a larger tolerance for risk than what might be assumed for a big government contractor.

“We want to move fast and hard, cautiously and consciously, but it’s OK if we fail every now and then,” Hernandez said, voicing a credo that aerospace engineers say held for the space program long before it became popular in Silicon Valley. “If we don’t, we’re probably not pushing hard enough.”