New biography explores the real-life Victorian horror behind Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’

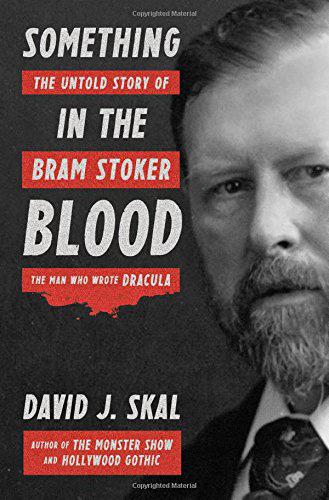

“Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, The Man Who Wrote “Dracula,'” by David J. Skal; Liveright (652 pages, $35) (Amazon)

October 31, 2016

By Mary Ann Gwinn

The Seattle Times

(TNS)

“Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, The Man Who Wrote “Dracula’” by David J. Skal; Liveright (652 pages, $35)

———

Several years ago, I read the book “Dracula” for the first time, expecting that Bram Stoker’s 19th century fable of blood, lust and the undead would be a quaint echo of Dracula’s many screen incarnations. I was astonished at its powerful sense of creeping, unstoppable horror, still spellbinding more than 100 years after its publication.

In “Something in The Blood: Bram Stoker, The Man Who Wrote Dracula,” David J. Skal, a cultural historian who appears to know everything worth remembering about author Stoker and his creation, has written an exuberant combination of biography and cultural history that thoroughly investigates the real-life horrors of the Victorian era that influenced the creation of the Count. Copiously illustrated, it is a keepsake for any Dracula enthusiast.

When Stoker wrote “Dracula,” he was a London theater manager whose work as a writer was completely eclipsed by his boss, the British actor Henry Irving, the man who changed his life.

Stoker was a dutiful child of Dublin’s middle class. Beyond the genteel precincts of Stoker’s Dublin neighborhood, the potato famine ravaged the countryside. Cholera killed with swift, horrifying brutality. In the city, cemeteries were so overcrowded, the decay of corpses threatened public health, and “resurrection men” routinely snatched bodies for medical instruction.

Stoker absorbed it all, but he continually set aside his writing to work another job, or three. A Dublin journalist, theater critic and civil servant, his life took a left turn when Henry Irving came to town — on the basis of Stoker’s adoring reviews, the English actor recruited him as his business manager and general factotum.

How exquisitely ironic that Stoker’s is the name most remembered today. In his lifetime, Stoker worked completely in Irving’s shadow. He managed Irving’s Lyceum Theater in London and published stories strictly as a sideline — tales of ghosts and monstrous horror, burbling out of his fertile, repressed Victorian imagination.

Skal goes at the Dracula story from every angle — its early inspirations, its reflection of Victorian England’s fears of sex, illness and Darwin’s theories. Victorians trying to hang on to the idea of God were more than ready to believe in a devil. He attempts to show that Stoker, if not a closeted gay man, preferred male company and loved men, including the poet Walt Whitman and the popular 19th century novelist Hall Caine, to whom “Dracula” is dedicated. It’s impossible to say. Stoker, a Victorian husband and father, never left any evidence that he expressed physical love for men.

Why did Dracula capture the public’s imagination? Certainly Stoker drew on every trick he had learned in the theater. He studied other epistolary novels (notably Wilkie Collins’ “The Moonstone.”) He soaked up “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” Irving’s interpretations of “Faust” and “Macbeth,” the fall of his friend Oscar Wilde and the real-life reign of terror of Jack the Ripper.

Skal believes Stoker would have been surprised as anyone at his creation’s literary immortality.

Caine, Stoker’s fast friend, wrote that Stoker was in it for the money. He “took no vain view of his efforts as an author,” Caine wrote. “He wrote his books to sell.”

“In the final analysis,” Skal writes, “the most frightening thing about Dracula is the strong probability that it meant far less to Bram Stoker than it has come to mean to us.”

———

©2016 The Seattle Times

Visit The Seattle Times at www.seattletimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.