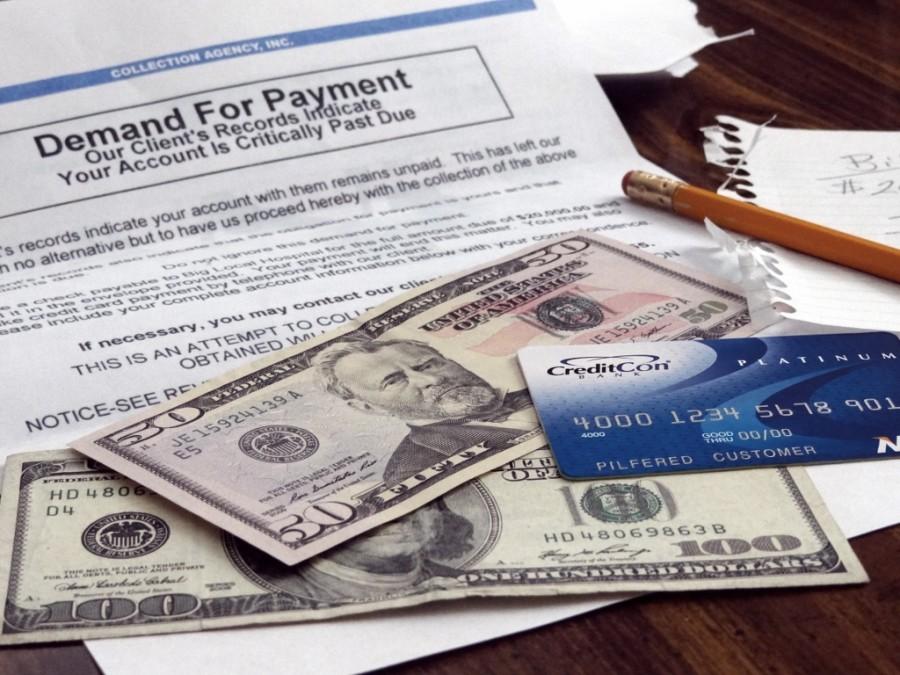

New credit card fraud protection creates confusion — even for FBI

October 20, 2015

By Iana Kozelsky

WASHINGTON — The FBI took a step backward over the past week in the effort to combat credit card fraud.

First, the agency told consumers a week ago that new microchip-installed credit and debit cards designed to better thwart fraud might still be vulnerable.

Don’t just sign your receipt, was the message of its initial warning. Use your PIN with the new chip cards because “these cards can still be targeted by fraud.”

But the FBI had to reverse field a bit this past week: It turns out that most of the new chip cards in the U.S. don’t use PINs.

The newly designed chips cards are known as EMV, a partnership of Europay — a European credit card company — MasterCard and Visa to establish an international security system for detecting credit card fraud.

The technology in the cards enables it to block information about a person’s credit card account, if hacked, from being used to replicate a counterfeit card for more purchases.

U.S. banks were supposed to issue new chip-installed cards by Oct. 1 to avoid fraud liability. The microchip has already been in use in Europe and elsewhere around the world.

The recent hacks of Target, Neiman Marcus and other big retailers have drawn attention to how widespread credit card fraud has become.

In 2012, of 23.8 billion credit card transactions, less than 1 percent — 13.5 million, or about .057 percent — were fraudulent, according to a study by the Federal Reserve System.

Likewise, less than one percent — .027 percent — of debit, prepaid and ATM transactions, which require PINs, were fraudulent.

The Federal Reserve found that fraud was more pronounced among signature and prepaid transactions than among those that used PIN numbers. “The percentage of signature transactions that were fraudulent was more than seven times that of PIN transactions in 2011,” it stated.

The “chip-and-PIN” method is the best security technology available, according to Brian Dodge, executive vice president of the Retail Industry Leaders Association, a trade group. He said banks that issue credit cards do not issue PINs with them, and card networks do not require PINs because there is no incentive for them to do so.

One of the two main card networks, MasterCard, allows, but does not require, consumers to choose between signing or entering a PIN when using the EMV chip, said Carolyn Balfany, a MasterCard senior vice president.

“Ultimately, it’s up to the issuing bank to decide,” Balfany said in an email. “Chip transactions protect consumers from counterfeit which is, hands down, the prevalent form of fraud in the U.S. PIN also protects against lost and stolen card fraud.”

While merchants realize PINs add extra security, the new method could result in consumer confusion, said Al Pascual, director of fraud and security at Javelin Strategy and Research, a financial consulting firm. Because swiping cards is more natural for users, a new maneuver and an extra step could cause “friction in checkout lines.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of merchants wait to turn on the new terminals until after Christmas,” he said.

The FBI’s revised warning this week added that customers will still be able to swipe the magnetic strip on their credit or debit cards if they choose, or if merchants have not yet installed upgraded payment terminals. However, the chip provides more security, the agency said.

The migration from the magnetic strip to the microchip needs to happen quickly, said Carol Alexander, a top marketing official at CA Technologies, a software company. Otherwise, the movement might fade out “like the integration of the metric system.”

———

©2015 McClatchy Washington Bureau

Visit the McClatchy Washington Bureau at www.mcclatchydc.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.