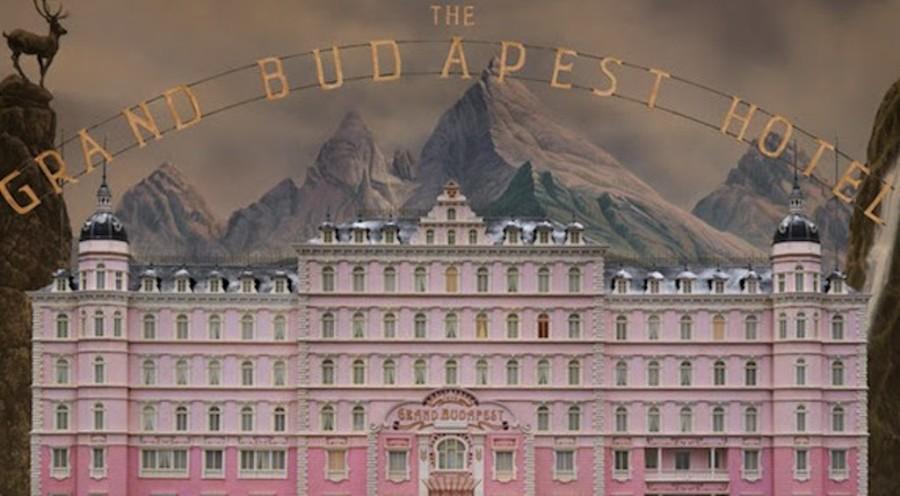

Wes Anderson Braces For Oscar’s Appraisal Of ‘Grand Budapest Hotel’

February 19, 2015

By Glenn Whipp

LOS ANGELES — If you watched the Golden Globes last month, you might remember co-host Amy Poehler joking that Wes Anderson, a filmmaker known for his meticulous, fanciful style, had arrived at the ceremony on “a bike made of antique tuba parts.” The camera caught Anderson not looking particularly pleased, though it wasn’t because of the joke. He was simply terrified at the possibility of having to deliver a speech at some point, which he did, marvelously so, when “The Grand Budapest Hotel” won the Globe for best comedy.

“These events are nerve-racking,” Anderson told The Times at Hollywood’s Egyptian Theatre last week. “At a certain point, you say, ‘I hope I don’t win because I don’t want to have to do this. Then as soon as you lose, the feeling rapidly changes and you think, ‘I would have been perfectly happy to give my speech. This … this doesn’t feel so good.’”

At the Oscars on Sunday, Anderson will have three occasions to feel apprehensive. “Budapest,” a captivating caper comedy about a high-level concierge, is up for nine Academy Awards, including three nominations for Anderson — picture, director and original screenplay. The 45-year-old filmmaker has been nominated before (screenplay nods for “Moonrise Kingdom” and “The Royal Tenenbaums” and as a producer of the animated film “Fantastic Mr. Fox”), but “Budapest” is his first to make the cut for best picture. And while he’s grateful for the recognition, he remains a little bemused by the academy’s embrace.

“It’s not like I had some feeling that this one is really going to knock their socks off,” Anderson says. “I could see the reaction to the movie — in not a terrible way — be where some people like it a bit more after a few years because it didn’t quite connect the first go-around.”

Those kinds of reappraisals have occasionally appeared in Anderson’s career, which began with 1996’s character-driven crime comedy “Bottle Rocket,” a movie that evolved from a 13-minute short film with the help of Hollywood heavyweight James L. Brooks. Accepting a prize for “Mr. Fox” five years ago at the Los Angeles Film Critics Association awards dinner, Anderson wryly noted the roller-coaster trajectory of reviews to that point, beginning with rapturous notices for such movies as “Rushmore” and “The Royal Tenenbaums” and then leveling off for 2004’s “The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou” and 2007’s “The Darjeeling Limited.”

Anderson’s deadpan readings of the barbs brought down the house, and though he did have to cherry-pick to find the bad notices (“Life Aquatic” and “Darjeeling” each have many ardent fans), there was an underlying acknowledgment that his professional progress had hit a speed bump or two at that time.

Anderson now says he made fundamental changes after “Life Aquatic” failed to connect with audiences. Ticking off the film’s budget ($53 million, which climbed to $60 million) and shooting schedule (100 days) with a morose disbelief that has persisted a decade, Anderson believes that “there were too many things about that movie that weren’t fun for me that I thought ought to be.”

He also notes that with “Aquatic,” he had miscalculated the kind of story he had, believing all the while he had made an ocean-going adventure movie with Bill Murray, kind of “an Errol Flynn thing … with pirates!”

“But it’s just not really that kind of story at all,” he says, likening the movie in reality to an ocean-going adventure made by idiosyncratic indie filmmaker Jim Jarmusch. “I remember showing Jim some scenes, and Jim’s reaction was, ‘Wow … weird … weird … interesting … poetic.’ And I thought, ‘If Jim Jarmusch thinks we’ve made a weird movie and we’ve spent $60 million, that’s a bad sign.’”

It was to be the last ill omen Anderson would encounter. Beginning with “Darjeeling,” a movie shot in India on a train, Anderson and his collaborators became even more meticulous in their pre-production planning — scouting and storyboarding and then taking those drawings and editing them into animatic scenes. The process becomes a precise road map for all departments, resulting in a rigor that, Anderson’s longtime producer Jeremy Dawson says, allows them to “never have to light a wall or room we don’t see or build the sets more than a few inches beyond where we need them.”

“All of these things save money and resources and make the shoot day focused on creativity and performances rather than logistics,” Dawson adds.

The films that have followed — the beautiful love story “Moonrise Kingdom” and now “Budapest” — are no less ingenious, charming and distinctly Wes Anderson creations, but there’s a richness of feeling beneath it all that has deepened too. Audiences took notice. “Moonrise” became Anderson’s biggest hit in a decade, and then “Budapest” turned into his most commercially successful film, grossing $175 million worldwide.

Both movies sport prominent connections with Anderson’s longtime girlfriend, Lebanese writer-illustrator Juman Malouf. Anderson dedicated “Moonrise” to Malouf and made “Budapest’s” bellhop, Zero, hail from her part of the world. “We’ve been together for many, many years, so her whole family background is my family background to me,” Anderson says. “That’s why this character is an Arab in the first place. Or a mixture of Arab and Jew.”

Anderson feels good about his recent success but notes that “you’d have to be pretty green to not be aware that it can blow over in about 15 seconds.” He’s working on two scripts, one a stop-motion animated film that he’s been writing with frequent collaborators Roman Coppola and Jason Schwartzman, lately working on train trips between New York and Los Angeles. (“It’s a thing I’ve found,” Anderson says. “Trains make for a great work environment. There’s no possibility of interruption.”) The other project is a live-action feature where, Anderson says, “the ingredients are there, but I haven’t stirred them around yet.”

One thing he won’t be doing, contrary to reports, is building a theme park with Devo co-founder and frequent Anderson composer Mark Mothersbaugh. Anderson recently wrote a foreword to a book on Mothersbaugh’s art, laying out a vision that included “hundreds of animatronic characters and creatures, rides through vast invented landscapes and buildings, extensive galleries of textiles and sculptures, plus an ongoing original music score piped in everywhere.”

“I thought it was clear that it was a metaphor, but somehow it got out that it was a genuine project I was trying to get funded,” Anderson says, laughing, later adding that Mothersbaugh has been approached by potential financial backers since the whimsical notion broke.

Because he’s as much a movie fan as anyone, Anderson is looking forward to the Oscars on Sunday on one level, because it affords him the chance to meet people he has long admired.

“I had never laid eyes on Clint Eastwood until this talk we did with the Directors Guild the other day,” Anderson says. “I asked him a lot of questions. I didn’t get any answers, but sitting between him and Rick (‘Boyhood’ director Richard Linklater) was like being between the two least stressful people I’ve ever met in my life. People could hit them with just about anything and they would calmly handle it.”

Even acceptance speeches?

“If you could put me between those two guys at the Oscars … well, I’d still be tense, but maybe just a little less so,” he says.

©2015 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC