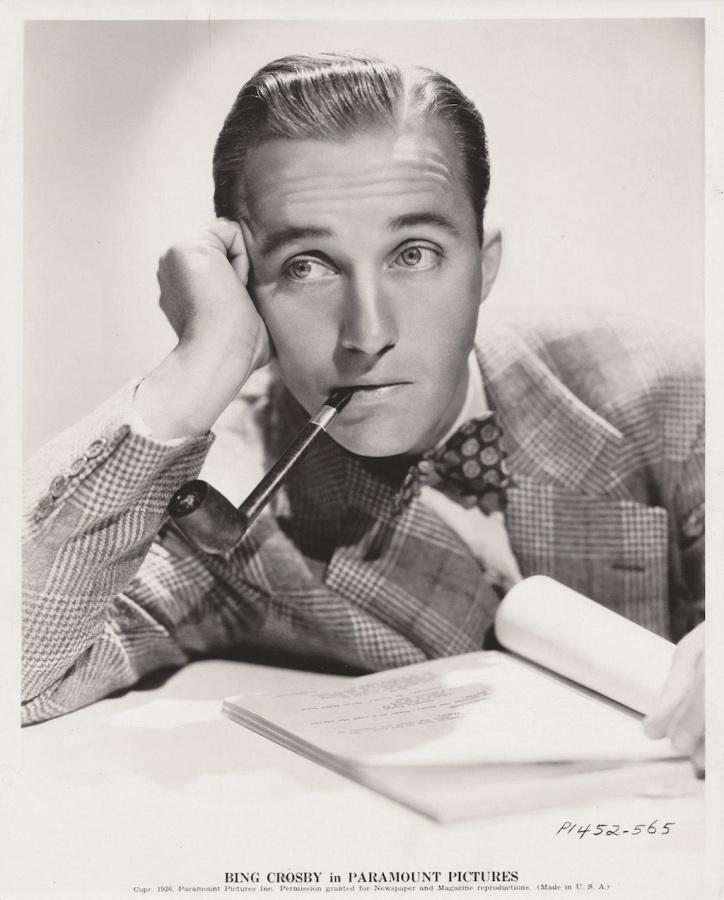

Bing Crosby Profiled In A Must-See Holiday Documentary

PBS’s new documentary “American Masters: Bing Crosby Rediscovered” airs Tuesday on PBS.

December 2, 2014

By Neal Justin

You could forgive Mary Crosby if she never wanted to hear “White Christmas” again. The most popular single in recording history was the signature hit for her father, Bing Crosby, and has become as tied to the holiday season as Santa Claus and fruitcake.

“For the first five years after his death, it was really painful to hear the song. I missed him so much, and I was in no way ready to lose my dad,” said Crosby, who was only 18 when her father died of a heart attack in 1977 on a golf course near Madrid.

“That time has passed. I’m so proud and happy to hear it now. It makes me feel good inside.”

Crosby’s change of heart is a big reason why we’re finally seeing “Bing Crosby Rediscovered,” one of the finest — and most significant — installments of PBS’ “American Masters” series.

The two-hour documentary, premiering Tuesday on PBS, should introduce a new generation to arguably the most underrated artist of the 20th century, a man who was to pop music what Elvis Presley would later be to rock ‘n’ roll. Inspired by Louis Armstrong’s phrasing, he brought jazz to the masses, becoming the most recorded singer of all time with nearly 400 hit singles. He was also a movie star, with a string of outrageous comedies with Bob Hope and three Oscar nominations, including a win as the affable priest in 1944’s “Going My Way.”

Twin Cities singer and jazz scholar Arne Fogel ranks Crosby with Armstrong and Charlie Chaplin among the most influential performers of the past 100 years.

“Jazz was very scary back then, especially in the Midwest. There was this racial aspect to it,” said Fogel, who hosts a weekly tribute to Crosby-era music on KBEM Radio (88.5 FM). “Then along comes this guy with a smiling-neighbor, movie-star guise. He was able to change mainstream pop music.”

But that side of Crosby may be unknown to anyone who wasn’t a teenager by the 1950s. By the end of that decade he was more famous for selling Minute Maid frozen orange juice than dominating the radio with that soothing, smooth bass-baritone voice. He also rarely pushed himself as an actor, relying on dry wit and his laid-back persona rather than digging deep. The biggest exception: his turn as an alcoholic has-been actor in 1954’s “The Country Girl.”

Part of his fade from superstardom was Crosby’s reluctance to bask in the spotlight. He and his family lived away from Los Angeles, and Crosby rarely mingled with the cooler, hipper members of the Rat Pack.

“When you think of Sinatra, you think of a man in a tuxedo with a microphone,” Fogel said. “When you think of Crosby, you think of a man with a hat and a fishing pole in his hand.”

Another factor: allegations of abuse by the children from his first marriage. Six years after his death, son Gary Crosby wrote “Going My Own Way,” a memoir that detailed incidents of being beaten with a belt dotted with metal studs. Two of his brothers confirmed the abuse, and later committed suicide. A fourth brother said the accounts were greatly exaggerated.

“Robert Trachtenberg (the director) really dealt with the elephant in the room, which was Gary’s book,” said his stepsister Mary. “I had lunch with (Gary) shortly after it came out, and he said agents told him he would sell more books if he made a bigger deal about it. My first thought was: How could you vilify your dad just to sell more books? My second thought was: Thank God my dad isn’t around to see a child betraying him. He wouldn’t have been able to deal with it.”

The three children from Crosby’s second marriage have never publicly said anything negative about their dad’s parenting. In fact, they’ve barely said anything at all. That’s another reason for Crosby’s low profile these days.

“Dad was really an under-the-radar kind of guy, and that’s what we believed in,” Mary Crosby said from her California home last week. (Characteristically, she downplays her own moment in the spotlight as Kristin Shepard, the character on “Dallas” who shot J.R. Ewing in one of TV’s most-watched episodes.) “It only took us 30 years to realize that we had done his legacy a terrible disservice. But we finally put it together.”

The film relies in large part on recordings, home movies and letters that were gathering dust in the basement of Bing Crosby’s second wife, Kathryn. She and her three kids with Bing all contributed to the film. Among the highlights: a letter in which he admits he didn’t think much of the script for the film “White Christmas,” a sequel to the far superior musical “Holiday Inn.”

Mary was impressed with the way Trachtenberg treated the family collection — as well as other aspects of her father that conflicted with his happy-go-lucky public persona. Viewers will meet a man who wasn’t always comfortable with others and cherished his private time.

“This movie doesn’t put Dad up on a pedestal,” Mary said. “He wasn’t perfect. But that’s fine. For those of us who knew him and loved him, this is great. But I’m really hoping this will reach a new generation.”

©2014 Star Tribune (Minneapolis)

Visit the Star Tribune (Minneapolis) at www.startribune.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC