Fungus Could Be The Help Agriculture Needs To Adapt To Climate Change

October 1, 2014

By Matt Campbell

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Imagine a world, just a few decades away, where once-fertile cropland is baked and starved of rain by ongoing climate change.

Just add fungus.

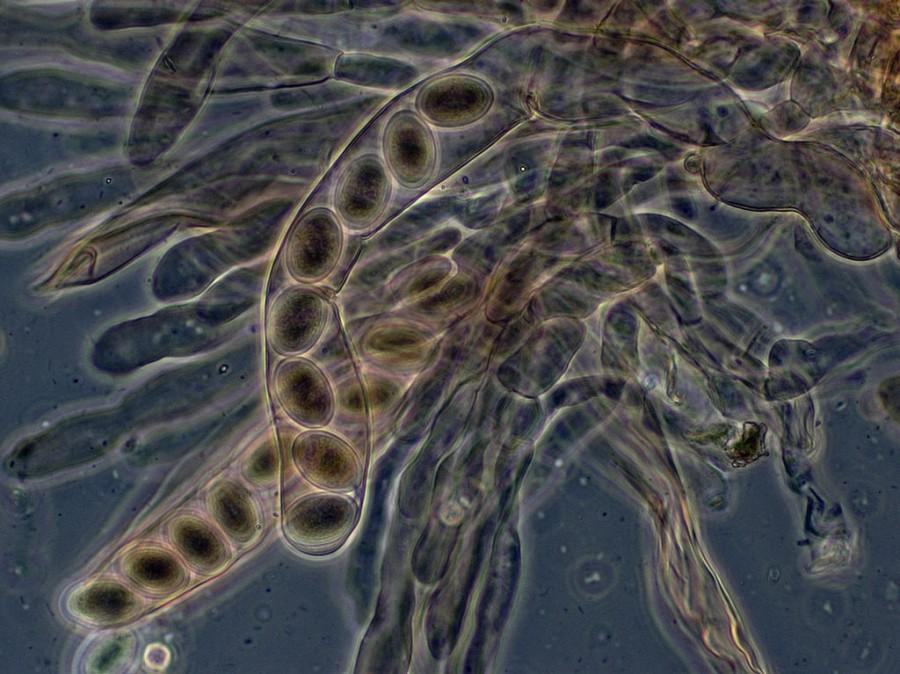

Scientists are discovering that microscopic fungi can help make food crops more abundant, less thirsty and more tolerant of rising temperatures.

Now, fungi-boosted seeds from a startup company are coming to market in Kansas and soon will be elsewhere. And one of the world’s leading agribusinesses is deeply invested in fungi and other microbial advances.

“It’s a bit of a paradigm shift,” said Brad Griffith, vice president of microbials for the St. Louis-based Monsanto Co.

The technology could make a crucial difference, considering the United Nations forecasts a need to increase food production by at least 60 percent to feed a projected 9 billion people by 2050.

Griffith said soybean farmers have been using microbials for several years to increase yields, but interest is rapidly growing in ways to help crops better withstand heat and salinity. Applied globally, that could make more land arable and help counter the effects of encroaching saltwater.

“Climate change has been a major motivator for us in moving forward with commercialization,” said Rusty Rodriguez, a microbiologist and chief executive officer of Seattle-based Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies, or AST. “We’re pursuing as aggressive an approach as we can. We see this as mitigating the impact of climate change on agriculture — until it gets too bad where it’s not going to matter.”

Rodriguez and his colleagues found that certain fungi found naturally in the soil allow plants to flourish under harsh conditions. They discovered this by looking at plants that thrive in Yellowstone National Park’s punishing thermal conditions.

Treating seeds allows microscopic fungi to colonize the root systems, conferring those adaptive abilities on food crops.

AST says field test results showed corn yields with the seed treatment increased 25 percent to 85 percent under drought conditions using 25 percent to 50 percent less water.

This was the third year of field trials, covering 14 states.

“We’re concluding these products will perform irrespective of soil type and climate zone,” Rodriguez said. “There is nothing yet telling us not to move forward.”

Because the seed treatment is an inoculant as opposed to a pesticide, it does not require regulatory approval in Kansas or Missouri.

AST has proprietary treatments so far for corn and rice and is working on soybean, wheat, barley, sugarcane, sorghum, leafy greens, tomatoes and citrus.

There are some skeptics, but the approach has caught the eye of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Last month, the agency, along with the governments of Sweden and the Netherlands, named AST among 17 initiatives out of a field of 520 “with high potential for transformative impact” for producing food with less water. That designation will come with a prize of between $100,000 and $3 million.

Zachery Gray, AST’s vice president for business development, said the young company has a letter of intent with a multinational distributor to sell its products.

Word of the microbial approach appears not yet to have penetrated mainstream agriculture. The Missouri Farm Bureau Federation, the Kansas Farm Bureau and the sustainability-preaching Land Institute, based in Salina, Kan., were not familiar with the technique.

“We always support the availability of new, innovative products that would help our growers produce their crops in a better way,” said Sue Schulte, a spokeswoman for the Kansas Corn Growers Association. “Until they get out into the real world — that’s when people really start to pay attention to how they work.”

Travis Harper, an agronomy specialist with the University of Missouri Extension office in Clinton, said farmers may have heard of the microbial approach but probably know little about it.

“We hear this type of thing from different companies and they’re excited about it and the farmers get excited about it,” Harper said. “Once these products are available to researchers, they sometimes confirm what the company is claiming and a lot of times they don’t.”

Fungi that colonize the root structure do not get into the food crops that are produced by the plants that host them, although they can be carried by way of the seed coating to the next generation. The fungi also can help plants draw nitrogen from the atmosphere, reducing the need for chemical fertilizers.

And the technique avoids the issue of genetic modification, which is a turnoff for many consumers.

“For 20 years or more, the multinationals like Monsanto have been talking about producing plants that are resistant to temperature, drought and salt by genetic modification,” Rodriguez said. “They have had limited success.”

But Monsanto late last year announced a $300 million “BioAg Alliance” with Novozymes of Denmark to focus on microbial products, including fungi and bacteria, for increasing crop yields.

Griffith said Monsanto will test microbial strains in more than a half-million plots next year and that number will expand exponentially.

“These things have been around for millennia,” Griffith said. “Our science is finally catching up. There are billions of microbes in a teaspoon of soil. But how do you know which ones are beneficial and serve a specific purpose? With our BioAg Alliance we’re trying to make good decisions based on DNA in the lab to identify which product candidates we can get out in the field.”

———

©2014 The Kansas City Star (Kansas City, Mo.)

Visit The Kansas City Star (Kansas City, Mo.) at www.kansascity.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services