Transistor Sister: Vintage Electronic Parts Become Chic Jewelry

September 29, 2014

SEATTLE — Steve Grzadzielewski has more than a million electronics parts lying around his house in West Seattle.

But he’s no engineer — Grzadzielewski and his sister Susan make and sell jewelry made out of vintage electronics parts. Their business, aptly named Transistor Sister, was founded in 1984, and it all started with a broken watch.

Steve Grzadzielewski watches his sister Susan Grzadzielewski and daughter Claire Montgomery make jewelry in his West Seattle home. Susan and Steve are the brother-sister team behind Transistor Sister, a business that uses vintage electronics parts to make jewelry. (Ellen M. Banner/The Seattle Times/TNS)

“It had all these little components in it, and they were pretty interesting,” said Susan, 56. “And I said, ‘That would make a nice earring.’ I put it through my ear. And then it was Steve. He was like, wow. Electronic jewelry designs.”

The duo began taking apart household items from telephones and calculators to washing machines and microwaves. They realized that the circuit boards they found were more than just functional — they were beautiful.

“I started looking at them as if they were objects and colors and shapes and textures just like you would any kind of art,” recalled Susan, who designs and makes Transistor Sister’s jewelry while Steve takes care of the business side. “When I used to go to Radar Electric (in Seattle), I’d take this in and say, do you have this in red? Do you have one of those in blue, I’d really like something in blue like that. And they would just look at me funny.”

By 1985, the Grzadzielewskis were traveling south to Silicon Valley to forage for parts. It was the beginning of the electronics industry in the area, and designs were changing so rapidly that companies would end up with thousands of obsolete or rejected components. Metals brokers bought up old circuit boards, made with gold, titanium and palladium, to wait for their value to rise. The Grzadzielewskis started there, paying anywhere from $20 to $40 for boxes of aesthetically pleasing capacitors, resistors, diodes and fuses. Some circuit boards cost 45 to 75 cents each, while others, like the first Intel processor, cost them $8 a chip because of the amount of gold.

With a variety of parts in hand, the jewelry design process began. Business took off immediately. The siblings recalled their first street fair on Mercer Island, Wash., before they had established prices for their pieces.

“We had to set the prices and I figured we’d start high,” said Steve. “Well, I didn’t know the demographics of Seattle. We had just moved here from the Midwest. These ladies were very well-to-do. So we were charging and they were paying all this money and I thought, Oh, my god, we’re going to be rich fast.”

At the height of their business during the late ’80s, Transistor Sister had 15 employees and 500 wholesale clients — including the Museum of Modern Art’s gift shop in New York City. Susan remembered putting in 70-hour weeks, and in 1989 the company was bringing in $350,000 in revenue. The siblings traveled all over the country, selling their jewelry at street fairs, art festivals, environmental and recycling events (“We were recycling before it was cool,” said Steve) and electronic and jewelry trade shows. Steve met John Fry of Fry’s Electronics in line for hot dog at a computer convention in San Jose, Calif. before Fry had opened his first store. The two hit it off, and Transistor Sister jewelry has been sold at Fry’s locations everywhere.

“The people who get excited about the jewelry are the people who are in the business or one of the tech companies, or people who are electronic engineers because they know that this stuff’s all vintage,” said Steve.

“I think those people are the most amazed,” added Susan, who believes that she and her brother never would have had the idea if they were engineers themselves. “It would never occur to them that it could be jewelry.”

In 1990, however, a recession hit. By1995 the siblings decided to disband and pursue other interests. Susan became an artist and paraeducator and Steve opened a neighborhood coupon business.

But because of continued interest in their jewelry, the Grzadzielewskis decided to bring back Transistor Sister on a limited basis in 2009. Their jewelry is now available on transistorsistor.com, on Etsy and in the gift shops of a few museums around the country, including the American Computer Museum in Montana. (There are no brick-and-mortar spots to get the pieces yet in Seattle, but Steve’s got his eye on the Living Computer Museum.)

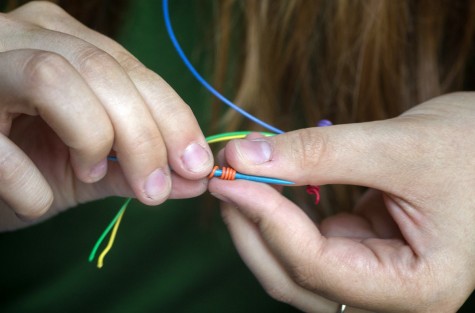

Claire Montgomery makes jewelry in the West Seattle home of Steve and Susan Grzadzielewski. Susan and Steve are the brother-sister team behind Transistor Sister, a business that uses vintage electronics parts to make jewelry. (Ellen M. Banner/The Seattle Times/TNS)

In the reboot, they’re still keeping it in the family. Steve’s daughter, 18-year-old Claire Montgomery, has taken an interest in the business and claimed Susan’s title of Transistor Sister (Susan is now Microchip Mama, and Steve is Diode Daddy). She and her boyfriend Chandler Holbert — she calls him Mr. Resistor — now help make and sell jewelry.

“It is a different generation,” said Susan. “These things are older than they are, some of these designs are older than they are, totally vintage. I think that’s what’s fun about bringing it back out.”

———

©2014 The Seattle Times

Visit The Seattle Times at www.seattletimes.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services