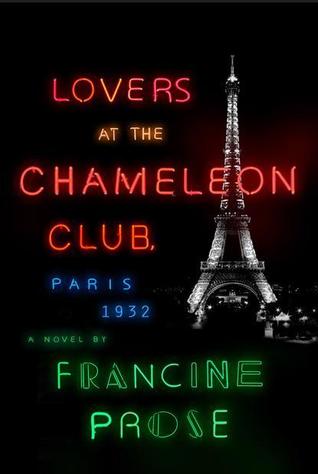

“Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932” by Francine Prose; Harper ($26.99)

———

“Police! Open Up!” is regularly heard at the door of the Chameleon Club, the fictional cabaret in Francine Prose’s new novel set in 1930s Paris. Unconventional verging on illicit, the club’s revue features sexually ambiguous performers who dance before a predominantly lesbian clientele — in an era when laws existed prohibiting a woman from dressing as a man. And yet the club is tolerated by authorities and celebrated by the city’s artists, intellectuals and aristocrats; “police!” is the ironic secret password they use to enter.

Who is found inside: Gabor Tsenyi, a young Hungarian photographer who captures the glamour and grit of Paris at night; Lily de Rossignol, a former bit actress spending her husband’s wealth on starving artists; Lionel Maine, a bawdy, abrasive American writer; Suzanne, Gabor’s French girlfriend; Yvonne, the club owner who provides safe haven to the outcasts who wash up at her door; Arlette, a small-hearted, marginally beautiful singer; and Louisianne Villars, a masculine former Olympic hopeful who goes by “Lou.”

Lou Villars’ unusual life, a puzzle, is at the center of the book. Sent away by her parents, she is brought up by nuns and trained to be a superior athlete, even performing before crowds in Paris. But that life is cut short and she begins another, working at the Chameleon Club, where she finds acceptance and her first girlfriend. Later she becomes an international auto racing champion, because when it comes to competition she always excels.

She’s not as good at personal choices: First she becomes an unapologetic German informant, then a Gestapo operative who tortures her fellow countrymen and women. She will die, we learn at the start, a violent death.

The character was inspired by the real-life Violette Morris, a French athlete/driver/Nazi collaborator. Prose first saw her in a photograph, “Lesbian Couple at Le Monocle, 1932,” taken by Brassai, a photographer best known for his shots of underground nighttime Paris. In the novel, Lou, dressed in a tuxedo, sits with her arm around Arlette, wearing a silk gown, and the photo is taken by Gabor.

“Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932” seeks, through multiple voices, to bring to life the person inside the tuxedo. What made her go from that moment of acceptance to betraying her country?

At the Chameleon Club, where Yvonne reigns like a 1940s film character, everyone comes into contact with Lou. A free, wild Paris emerges in the collage of personal narratives, which appear in the text as various documents.

Lionel rants in essays about Suzanne, the lover he loses to Gabor. Suzanne, in an unpublished memoir, recalls what it’s like to love an artist. In letters home, Gabor writes about his work. Lou’s life is detailed by her untrustworthy biographer, Nathalie Dunois.

“Without claiming too much for my little book, I will only say that I have tried to make my humble contribution to the literature on the mystery of evil,” Dunois writes. Her book, “The Devil Drives: The Life of Lou Villars,” spells out the most intimate parts of Lou’s story — parts that Dunois herself admits she is forced to invent. She’s not a great biographer — the closest she gets to explaining the root of Lou’s evilness is that she has been rejected.

Overall, the book is a bit light on insights and a little heavy on caricature. Take, for example, this description: “(E)veryone recognized Chanac, principally because of his trademark mustache, which he waxed into points and teased perpetually, with one finger, like someone plucking a violin string.” Would you guess that Chanac is a corrupt police official? Of course you would.

Prose, a National Book Award finalist (for the novel “Blue Angel”) and nonfiction bestseller (“Reading Like a Writer”), should be able to tackle just about any literary project. However, she doesn’t quite meet the challenge presented by telling her novel through written artifacts. The multiple voices tend to blend together. Even Lionel, as the Henry Miller stand-in, lacks distinctive prose.

“One day, in the near future, I will have to leave Paris. If I let the thought cross my mind, I won’t sleep for the rest of the night,” he writes. “The gloom and doom economy, the coming war, unemployment, riots, street crime, financial scandals, serial killers, Nazis at home and next door — what red-blooded Parisian male would admit to noticing or caring? The women worry constantly, as women always do.” Miller’s misogyny is there but without the vigor that made his writing popular.

The first-person narratives are limiting. Emotional and intellectual lives are articulated only as they would be expressed to their intended audiences, leaving “Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932” flat, without resonance.

The complex structure plays out in a straightforward chronology, without much contradiction, driving toward the same end. Everything feeds the book’s own plot, following Lou to her last days. And yet she remains absent. The story circles around Lou Villars, who in the end is less interesting than the people around her and perhaps less complex than her inspiration, Violette Morris.

———

©2014 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services