By Michael Doyle

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court seemed split down the middle Monday, and occasionally lost in the fog, as the justices confronted a challenge to the Obama administration’s greenhouse gas regulations.

Conservatives, including the court’s frequent swing vote, Justice Anthony Kennedy, periodically shared the skepticism of Texas Solicitor General Jonathan Mitchell, one of two attorneys arguing against the Environmental Protection Agency’s greenhouse gas rules.

“I couldn’t find a single precedent that strongly supports your position,” Kennedy bluntly told U.S. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli Jr., who was representing the EPA regulators.

Coming at the end of an unusually long oral argument of nearly 100 minutes, Kennedy’s flat-out declaration, combined with justices’ earlier questions and remarks, suggested an eventual ruling against the EPA, perhaps along familiar 5-4 lines. Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. and, more emphatically, Justices Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito also sounded skeptical about the agency’s greenhouse gas actions that are being challenged.

The court’s four Democratic appointees were more sympathetic to the EPA rules, which included revising specific emission standards spelled out by Congress.

“Why shouldn’t we defer to the agency?” Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked.

Sotomayor’s question reached the heart of the legal matter argued Monday, and hinted at the potential political fallout. Those challenging the EPA’s regulations argue, in part, that executive branch officials overstepped their bounds in interpreting a law passed by Congress. An eventual ruling against the EPA might fuel Republican critics who already contend that the Obama administration too often acts unilaterally.

“The optics of this case are as equally important as the law,” William J. Snape III, a fellow and practitioner in residence at American University’s Washington College of Law, said after the argument.

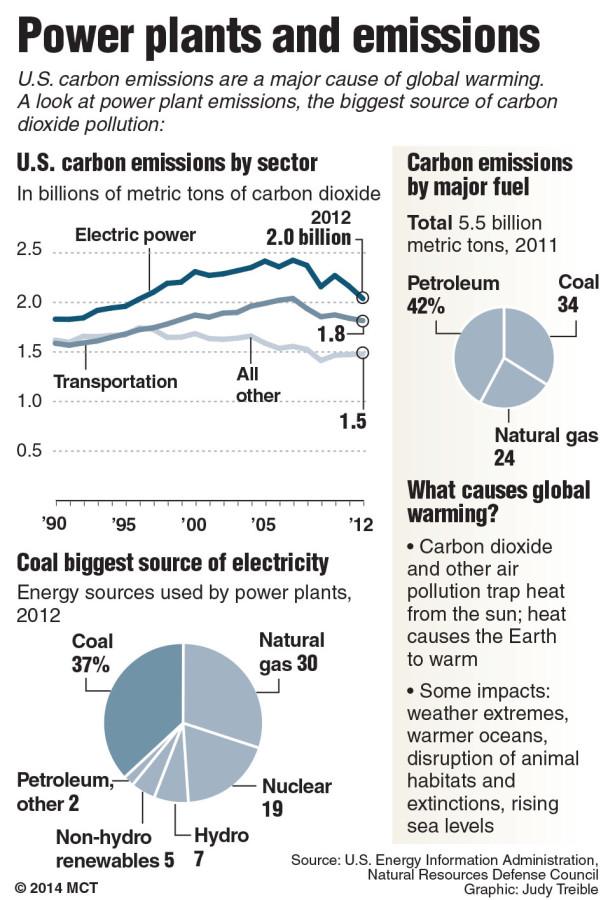

The frequently technical argument Monday, though, also made clear that the EPA will retain the ability to regulate greenhouse gases from stationary and mobile emission sources even if the court strikes down the regulations in question. Justices showed little interest in reversing a 2007 high court ruling that first declared the EPA had the authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

Mitchell, in a legal brief filed on behalf of Texas and other states, had initially floated the possibility that the Supreme Court might overturn the earlier decision. The idea was essentially ignored Monday.

“I was in the dissent in that case,” Roberts noted, “but we still can’t do that.”

Using Clean Air Act provisions that aren’t being challenged before the Supreme Court, the EPA by some estimates will still be able to regulate 83 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Verrilli acknowledged Monday that the regulations being challenged will increase this only to about 86 percent.

The regulations challenged Monday stem from a particular part of the Clean Air Act. The law sets 100 or 250 tons per year, depending on the source, as the pollutant emissions threshold for when “Prevention of Significant Deterioration” permits are needed. For greenhouse gas emissions, which result from many sources, the EPA changed this to a more lenient 100,000 tons per year.

Conservatives objected, even though the less onerous standard imposed a smaller burden on industry. Regulators, the critics say, shouldn’t unilaterally rewrite congressional work.

“Congress does not establish round holes for square pegs,” Mitchell said Monday, adding that “in these situations (an) agency cannot make a round hole square by rewriting unambiguous statutory language.”

While an activist dressed in a polar bear outfit paraded on the Supreme Court steps outside, Verrilli declared inside that environmental regulators have acted reasonably in response to a serious threat.

“It is the gravest environmental problem that we face now,” Verrilli said, “and it is one that gets worse with the passage of time.”

Justice Clarence Thomas, as is his habit, was the only one of the nine justices not to speak or ask questions during the oral argument. A decision in the case is expected by the end of June.

—

©2014 McClatchy Washington Bureau

Visit the McClatchy Washington Bureau at www.mcclatchydc.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services