By Rob Hotakainen

WASHINGTON — A bidding war of sorts has broken out in Washington state, where politicians are scrambling to raise the state’s minimum wage of $9.32, already the highest in the nation.

Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee, who went to the White House on Friday to discuss the issue, wants a minimum ranging from $10.82 to $11.82 per hour.

A group of state House Democrats wants it to hit $12 an hour by 2017.

And the new Seattle mayor, Ed Murray, has endorsed an even higher minimum wage: $15, matching the rate approved by voters in the small airport city of SeaTac in November.

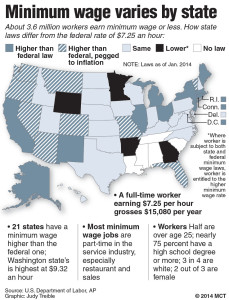

On the other side of the country, official Washington is watching closely, ready to spotlight the state as the U.S. Senate prepares for a March vote to raise the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10, a plan that has won strong backing from President Barack Obama.

“Washington state gets it — politicians in Washington, D.C., should, too,” said Josh Goldstein, a spokesman for the AFL-CIO. He called the state “a leading example of what’s possible for the rest of the country.”

But increasing the wage rate for the nation’s poorest workers could be a heavy lift, both in Washington, D.C., and in Olympia.

On Capitol Hill, opponents got new ammunition on Tuesday from the Congressional Budget Office, which said U.S. businesses likely would shed a half-million jobs by 2016 if Congress approves the higher minimum wage.

Two of the state’s top Republicans in Congress, Reps. Doc Hastings of Pasco and Cathy McMorris Rodgers of Spokane, both say they’re ready to oppose an increase. Both represent districts in the eastern part of the state, where the cost of living is lower and median household incomes generally are below state averages.

In Washington state, raising the minimum wage is proving to be a tough sell, with many who fear that the higher cost of labor already is chasing jobs to nearby border states.

“When Idaho has a $7.25 minimum wage just a few miles away, it can have a significant impact on where businesses locate,” said Republican state Sen. Michael Baumgartner of Spokane.

Democratic Sen. Patty Murray of Washington state said that an easy way to end the disparity would be for Republicans to accept the $10.10 federal minimum, which would apply to all 50 states. And she wants the wage rate indexed to inflation, which would result in automatic increases, matching the system in place in Washington.

“I think our state prides itself on leading the way and showing that our workers are valued,” said Murray, a veteran member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, which is expected to approve the plan before it goes to the full Senate for a vote next month.

A former preschool teacher, Murray is eager to teach Congress her version of a lesson: Paying employees the current federal minimum wage, which computes to $15,000 a year, is a good way to guarantee that people stay in poverty and ultimately hurts the U.S. economy.

“If you’re earning $15,000 a year, you are not going to a movie, you are not going to get ice cream for your kids, you’re not buying any extra clothes,” Murray said. “But when you put a little bit of money in people’s hands, then they can make those purchases that are actually good for businesses and allow them to grow and hire more people.”

After meeting with Obama and other administration officials on Friday, Inslee said it makes no sense to have people working 40 hours a week and still be forced to rely on public assistance to get by.

“When people can’t eat, they’re not good consumers,” he told reporters.

And Inslee, a former congressman, dismissed the Congressional Budget Office report, citing other studies that show any job loss would be minimal: “With all due respect, they are not the experts on this issue.” He noted that just last month, seven recipients of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences recommended raising the minimum wage.

A raise would be welcome news for Martina Phelps, who earns $9.32 at a McDonald’s restaurant in Seattle. She lives in a two-bedroom apartment with seven relatives. If she gets a raise, she said, she’d like to get a place of her own, maybe even go to college and buy a car.

“There’s people at my job that have master’s and bachelor’s degrees and they’re working at McDonald’s, being managers,” said Phelps, 21, of Skyway, Wash. “Some of them have two jobs. And it’s like, why are we still at the bottom?”

Opponents of a higher minimum wage argue that unemployment already is too high in Washington state. In December, it ranked 29th among the states, with a rate of 6.6 percent.

Hastings, the longest-serving Republican in the state’s congressional delegation, voted against a higher minimum wage in 2007, the last time Congress raised it. And he said that raising it now would make it harder for hundreds of thousands of unemployed Americans who are looking for entry-level jobs and for employers who are trying to adjust to the federal government’s new health care law.

“Obamacare is already hurting Americans’ pocketbooks by cutting employees’ hours and shrinking their take-home pay,” Hastings said.

And McMorris Rodgers, who also opposed a higher minimum wage seven years ago, said that Congress should eliminate regulations and improve job training instead of just raising the cost of labor.

“We need to focus on long-term job growth, not an ineffective, short-term fix,” she said.

Amid all the clamor to raise the minimum wage, Baumgartner is going against the grain. He said the state’s higher minimum wage also has resulted in one of the highest unemployment rates for teens in the United States, at more than 30 percent. And he has introduced a bill that would lower the mandatory wage for teens working summer jobs to $7.25 an hour so that more employers can afford to hire them. Critics responded to a similar bill last year by suggesting that state lawmakers approve a lower “training wage” for new legislators.

“I hear from parents all the time: Their kids can’t find work and they sit around playing video games and going to the mall,” Baumgartner said. “We’re just not giving people the ability to develop a work ethic.”

Murray said Washington state’s experience has shown that a higher minimum wage is good not just for workers, but for companies, too: “What our employers here know is that if they pay a good wage, then they have workers who can actually buy their products, and that is good for our businesses.”

In his State of the Union speech last month, when the president urged Congress to “give America a raise,” Obama praised Costco, a company headquartered in Washington state, for using higher wages as “a smart way to boost productivity and reduce turnover.” And on the day after his speech, Obama visited a Costco store in Maryland to make his case for the higher minimum wage.

Baumgartner, who lost a bid to join the U.S. Senate in 2010, said there’s an easy explanation for why Washington state is witnessing the bidding war over the minimum wage: The state is dominated by Democratic politics, with no Republican candidate winning the governor’s seat since 1980, giving the GOP its longest losing streak for any state.

Obama agreed on Thursday, saying “it’s no surprise” that most of the states with higher minimum wages are governed by Democrats.

But even if they can’t raise the minimum wage, Baumgartner said, Democrats are eager to use the issue to position the party for the 2014 elections, confident that it will appeal to women and others.

Murray said there’s no doubt that that the minimum wage is “a women’s issue” because a majority of minimum-wage earners are women. And she said it’s sure to play well with voters, along with bread-and-butter issues such as higher education and job training.

“These are issues people understand,” Murray said. “It means we’re talking about them and their security in this country, and obviously those are good issues.”

Phelps, who appeared at a news conference with Murray this week to promote the issue in Seattle, has worked at McDonald’s since September.

In an interview, she said she receives a paycheck of $564 for her net pay for 80 hours of work every two weeks. She said minimum-wage workers definitely need a raise.

“We’re not trying to buy Ferraris and go to Hawaii and go on big vacation trips and buying mansions, we’re just trying to live,” she said.

———

(David Lightman contributed to this report.)

———

©2014 McClatchy Washington Bureau

Visit the McClatchy Washington Bureau at www.mcclatchydc.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services