By Emily Alpert

LOS ANGELES — Bryan Piperno was just 9 years old when he began keeping his secret.

The Simi Valley, Calif., youngster tossed out lunches or claimed he ate elsewhere. As he grew older, he started purging after eating. Even after his vomiting landed him in the emergency room during college, he lied to hide the truth.

Piperno, now 25, slowly fended off his eating disorder with time and care, including a stay in a residential treatment facility. But surveys show a rising number of teenage boys now struggle with similar problems.

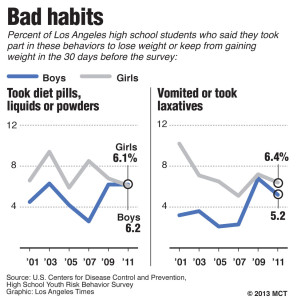

High school boys in Los Angeles are twice as likely to induce vomiting or use laxatives to control their weight as the national average, with 5.2 percent of those surveyed saying they had recently done so, according to the most recent survey data gathered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Los Angeles Unified School District. They are also more likely to have used diet pills, powders or liquids than boys nationwide.

The numbers challenge old assumptions that boys are immune to a problem better known to afflict teenage girls. Girls still exceed boys in fasting to lose weight, but the latest data, from 2011, showed that Los Angeles boys were nearly as likely as girls to purge through vomiting or laxatives. They were also as likely as girls to use diet pills, powders or liquids without the advice of a doctor — 6.2 percent said they recently used such substances, compared with 6.1 percent of girls.

Some experts say boys are starting to face the pressures long placed on girls, as buff, bare men proliferate in pop culture. Boys today watch Channing Tatum strip as “Magic Mike” or weigh themselves against the muscular Dwayne Johnson. The nonstop chatter of Twitter and Facebook has amplified those messages, therapists say.

“Boys are growing up now with the billboard of the guy with perfect pecs and biceps,” said Roberto Olivardia, a clinical instructor in the Harvard Medical School psychiatry department. “You just didn’t see that years ago.”

Teenage boys say abs are prized and ogled. Andrew Shrout, a 19-year-old junior at the University of California-Berkeley, said boys felt they needed to be very lean at his former high school in Long Beach, Calif. “Men are pressured to have as little fat as possible — but you’ve got to pretend like you don’t watch what you eat,” Shrout said.

He decided to lose weight for his health but also because another guy on the water polo team used to grab his stomach and jiggle it. “I can see why a lot of younger kids get sucked into a vortex and end up doing bad things,” Shrout said.

Steroid use is also on the rise among Los Angeles teen boys, the survey found, with roughly one out of 20 saying they have used steroids — only a slightly smaller percentage than those who had recently turned to diet pills, powders or liquids.

Sports can pile on more pressure. Wrestlers, for instance, often aim to lose enough weight to grapple with lighter opponents. For some competitors, throwing up or downing laxatives can be a gateway to a disorder that lasts beyond the sporting event, said Dawn Theodore, clinical director of the Eating Disorder Center of California in Brentwood.

Los Angeles isn’t the only city where boys have been increasingly likely to purge or turn to diet substances, with higher-than-average rates also seen in Chicago, Houston, Charlotte, N.C., and elsewhere. Government estimates show that the number of males hospitalized for eating disorders rose 53 percent between 1999 and 2009. Some experts say they are unsure whether more boys and men are in fact suffering such disorders or whether more are now willing to seek help.

Females remain much more likely to be hospitalized for eating disorders than boys and men, who made up 12 percent of such hospital stays as of four years ago, the government estimates show. However, researchers say that because men fear coming forward, the rates among males might be higher than the numbers suggest.

When they finally get help, the boys’ cases “tend to be especially severe,” said clinical psychologist Jennifer Henretty, who directs intensive outpatient programs at the Center for Discovery, a national system of eating disorder programs. “People don’t look until it’s really out of hand.”

Experts say part of the problem is that traditional methods of detecting disorders were made with girls and women in mind.

Benjamin O’Keefe, 18, remembers Googling the word “anorexia” and finding a website that said it halts menstruation. “There was nothing targeted at me,” said O’Keefe, who struggled with the disorder in high school in Florida.

He exercised constantly and sometimes ate only a cheese sandwich for days at a time. He suffered massive headaches, slept incessantly and fainted onstage while rehearsing for a play.

While he weakened, “people were saying, ‘Wow, you look great,’” O’Keefe remembered.

He began talking about his past struggle with anorexia upon launching a petition earlier this year urging Abercrombie & Fitch — known for its shirtless models — to carry larger sizes.

(EDITORS: STORY CAN END HERE)

Men who battled anorexia or bulimia as teens told the Los Angeles Times that other problems often drove their disorders. Piperno, the Simi Valley man, said it began as a way of exerting control over his body after suffering sexual abuse.

Matthew, a 20-year-old who faced anorexia as a teen in the Pasadena area, first avoided eating to “numb out” the alcoholism of his father and stepmother.

“It’s not about the body,” said Matthew, who spoke with the Times on condition that his last name not be used. “It’s a mental issue — it just manifests itself through the body.”

As awareness has grown, more recovery programs have begun accepting men: Leigh Cohn, a Carlsbad writer and publisher of books on eating disorders, said his analysis of advertisements in his resource catalog showed that the share of treatment facilities that admit men jumped from 35 percent to 69 percent between 2000 and 2013. Yet families say it is still hard to find help for boys.

When a family near Griffith Park grew worried about their son, a skinny middle-schooler who refused breakfast and ran constantly, their doctor waved it off, saying he seemed fit. The family, which spoke to the Times on the condition of anonymity, later sent the son to a center where he was the only teenage boy. “I couldn’t really relate to anyone,” the boy said.

After switching programs, he met other boys and began to recover. Matthew ended up crossing the country for a residential program where men were all on the same floor with their own therapist.

California middle and high school health classes cover eating disorders, but the increases may be a sign that more tailored lessons are needed, said Lori Vollandt, Los Angeles Unified health education programs coordinator. “This is probably something we need to look at further,” she said.

©2013 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services

Charts showing percent of Los Angeles high school students who said they partook in risky behaviors to lose weight or keep from gaing weight according to a survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and prevention.Los Angeles Times/MCT