By Christopher Borrelli

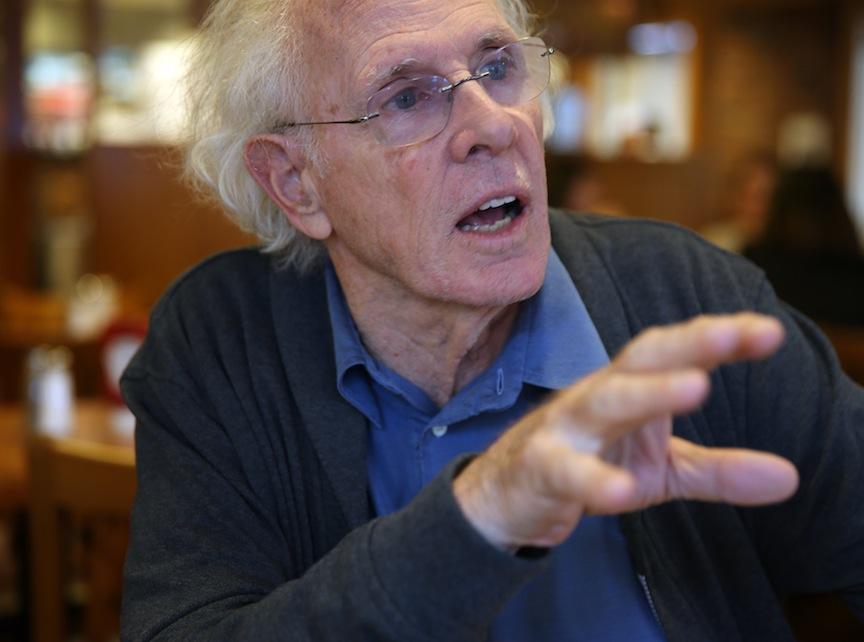

CHICAGO — Bruce Dern runs.

Almost every day.

He has run most of his life. A former track star at New Trier Township High School in Winnetka, Ill., in the late 1950s, he tried out for the Olympic team in 1956 (but finished ninth in his division). On camera, though, Dern, who is 77 now, is much more pokey.

In “Nebraska,” the new Alexander Payne movie for which Dern won the best actor award at the Cannes Film Festival in the spring, he moves with a paradoxical mix of tentativeness and inertia, the loose jocularity of his 1970s oddballs replaced by an elderly man who appears determined to get somewhere, and just as determined not to reveal the strain on him. Dern plays Woody Grant, a Midwestern octogenarian crank who insists on traveling from Montana to Nebraska to collect $1 million promised by a junk-mail sweepstakes. Woody will walk if no one will drive. No one will.

His wife (June Squibb) tells him he’s nuts; his oldest son (Bob Odenkirk) wants no part of it. But then his youngest (played by former “Saturday Night Live” star Will Forte) gives in, considering it an opportunity to bond. During the brief road trip, there’s a scene in which Dern ambles across the empty bedroom of an old farmhouse. The home was owned by Woody’s parents. He seems haunted, crosses to an upstairs window, stares out and says if his parents knew he was there he’d be whipped. But there’s no one to whip him now.

“The most honest parallel between my life and my career is that scene,” he said.

As a child, Dern wore white gloves to dinner. He raised his hand before being acknowledged by his parents. He lived in Glencoe, Ill. His home was built by renowned architect Louis Sullivan. His bedroom overlooked Lake Michigan. He has a pedigree. The last time Dern spoke to his mother, in the early ‘70s (she died soon after), she was still trying to get him to move back to Chicago, he said. “I think I was being groomed to take over the store,” he said.

Meaning, the Carson Pirie Scott department store chain, which his great-grandfather founded.

Though it was still relatively early in his career, Dern was established: With close friend Jack Nicholson, he made “Drive, He Said” (1971) and was shooting “The King of Marvin Gardens” (1972). He had a sci-fi blockbuster in theaters, “Silent Running” (1972). By the end of the decade, he would be a best supporting actor Oscar nominee for “Coming Home” (1978). He would be reunited with his “Marnie” director Alfred Hitchcock for “Family Plot.” But he made his reputation working with low-budget king Roger Corman. He lost his head in a movie. Ate a baby. Tried bombing the Super Bowl (“Black Sunday”). He had a knack for playing unhinged.

And it stuck.

Even his mother asked: Hadn’t he shot John Wayne in the back and killed him? He had, in “The Cowboys” (1972): “I said, ‘But it’s a movie, mother.’ And she said, ‘Oh, Bruce, your grandfather will never understand.’”

Indeed, talk to Dern long enough and you realize that his role as Tom Buchanan, son of privilege in the 1974 adaptation of “The Great Gatsby” — one of the few times he was cast against type — was eerily spot-on.

“Dad’s history is incredible,” said actress Laura Dern, his daughter with first wife Diane Ladd. “When you come from that kind of money, there is a classism you are raised around and a pressure to continue the lineage. But he prided himself on going against it. And he had political lineage, business lineage — and he becomes an actor! The ultimate rebellion! My mom is from small-town Mississippi, and that’s phenomenal, but Dad, to have stature waiting, then take the road less traveled? It cost him. His parents never accepted acting. But it’s beautiful, right?”

Chances are, if you have thought at all about Bruce Dern in the past 30 years, everything you assumed you know is quite wrong: You know him as a quintessential supporting actor, a consummate scene stealer. But just as often, he does a lot without doing much, said filmmaker Joe Dante, who directed Dern in several films, including “The ‘Burbs” (1989) with Tom Hanks.

“Which is never the most noticeable quality,” Dante said. “But when I first saw him, which is when a lot of people first noticed him, in the 1960s, he had this acting style that no one else had. He could channel the ticks of real people. His vocal mannerisms were natural and unique. He always seemed more in the moment than anyone else — it’s remarkable to think that a guy who has never drank, smoked or taken drugs could capture the psychedelia of the ‘60s in a movie like ‘The Trip’ (1967).”

“Bruce is no lunatic,” said Squibb, who is 84. “I always thought of him as that wonderful actor who never got a chance. But that’s not even as surprising as, once you know about his family, how much of his childhood he lost and the relationship he had with his proper parents — kind of strained — how less than proper he is.”

©2013 Chicago Tribune