What to play: ‘Wilmot’s Warehouse,’ a puzzle game about sorting for our Marie Kondo age

October 3, 2019

Life is a mess. And within that big mess is a bunch of little messes.

I’m writing this from my bedroom, with a view straight into my disaster of a closet. It stresses me out. I’m sure my cat sitter looks at my loosely organized piles of stuff — T-shirts, sweatshirts, pants, books, old video game consoles, CDs I haven’t stored — and wonders how I’ve managed to become an adult. I worry too that my cat is silently judging. What was yesterday a nook for napping can tomorrow be a jumble of extension cords.

So the very concept of “Wilmot’s Warehouse,” a game for our Marie Kondo-influenced age, seems to contradict my lifestyle. For “Wilmot’s Warehouse” is a game about organization, specifically creating order and then frantically trying to remember said system of order. It seems, on the surface, a little like work. Unlike work, however, or even cleaning my closet, I found it relaxing. Mostly.

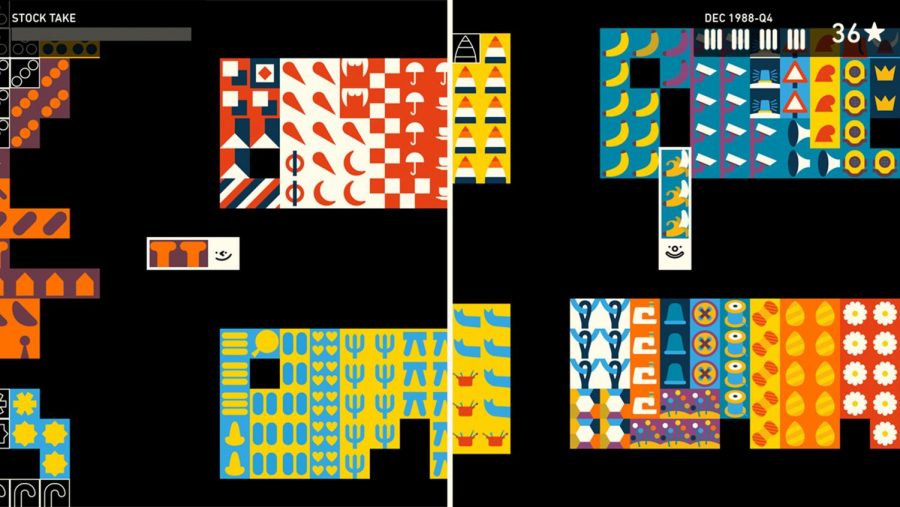

Wilmot, the good-natured block we control, is employed at a warehouse. Wilmot’s boss rewards him with more work and sometimes not-helpful motivational posters — remember, for instance, to lift from your knees rather than your back. Unlike Wilmot, said boss isn’t seen careening around the warehouse, which is presented as a giant black arena with some boxy areas to drop off items.

It’s simple and elegant, and that should be no surprise. Its designers — Ricky Haggett and Richard Hogg — were principals on “Hohokum,” a charming, languid, text-free storybook that celebrated the joys of discovery via colorfully abstract objects and creatures. “Hohokum” looked like a gallery piece, with characters that took inspiration from the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” film.

“Wilmot’s Warehouse” — for PC, Mac and Nintendo Switch — is a bit more, well, workmanlike, with Wilmot starting the day with a smile and often becoming stressed and sweaty throughout its challenges. The pitch is straightforward: Each level starts with a truck dropping off a bunch of items. We organize them, and then once the clock ticks we have to remember where we placed them and deliver them.

Sometimes what the items are seems relatively obvious — a chess piece, for instance, or a Christmas tree. Other times, they look like abstract blobs. You may see a kitchen utensil or a sailboat. I may see a computer mouse or a shark’s fin. In this way, at times “Wilmot’s Warehouse” becomes a game of pareidolia, toying with the human ability to assign story and patterns to lines and triangles.

There are times my own mind started to play tricks on me.

If I set the game down for a day or so and later returned to it, I would start to question my own organizational skills. What I once characterized as Christmas wrapping paper now so obviously looks to be a rabbit. And now Wilmot is frantically racing around the warehouse trying to fulfill a delivery but not knowing where to go. Wilmot had left the “pet” section I created in my facility empty because what it needed was over in the “holiday” area.

But it’s oh so fulfilling when the job is complete. Irresistible too is the chill-out electronic music and the little bouncy ping that occurs when Wilmot connects items of the same type together.

“Wilmot’s Warehouse” makes cleanliness a joy, in part because it’s not really about tidying up. The challenge is in recalling the stories and definitions we ourselves assign objects and remembering that even when life isn’t a mess, our mind has a tendency to cause one.

In that way, it may not be all that different from cleaning, where an entire chore can be derailed by the memories triggered by uncovering an item from our past.