‘Shoes’ Unveils Mystery, History Of Footwear

February 12, 2015

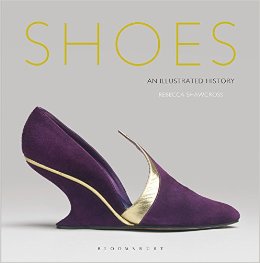

“Shoes: An Illustrated History” by Rebecca Shawcross; Bloomsbury (256 pages, $40)

———

“Shoes: An Illustrated History” by Rebecca Shawcross shows the human fascination with footwear over millennia.

It starts in primitive times, when all humans wanted was to keep his or her feet from becoming bruised or chilled. It runs through the latest fashions.

It also shows how some shoe styles have tortured your tootsies. (High heels, I’m looking at you.)

Shawcross is the Shoe Resources Officer at The Shoe Collection at the UK’s Northampton Museum. Starting back in the early 1200s, Northampton was a center of shoemaking in the UK, so the museum has an extensive collection of styles.

“Shoes” is a heavily predominately Western survey of shoe history. There is only one example of the Chinese shoes made for a woman’s bound — and broken — feet.

“Although the debase rages as to how many true shoe types there are,” writes Shawcross, “it inevitably boils down to just seven or eight: the sandal, the moccasin, the court shoe, the lace shoe, the monk, the leg boot, the bar shoe, the clog and the mule.”

In “Shoes,” the earliest examples start with early man.

In 1991, the mummified body of a Neolithic hunter from the Copper Age (around 3300 B.C.), dubbed Otzi, was discovered half-buried in a melting glacier by hikers in the Alps.

In 2005, a professor Hlavacek recreated his shoe wear, saying, “Leather laces attached to Otzi’s goatskin leggings would have been tied to the shoes in order to prevent the leggings from riding up Otzi’s legs.”

Coming closer to the modern era is the Egyptian straw sandal circa the 19th century B.C., and the Coptic woman’s leather sandal from about the 6th century A.D. They all look uncomfortable.

When you hit the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, there are more shoe styles and choices for adornment (embroidery, studs). The European aristocracy and the rising middle classes who could afford more than one set of shoes prized glitzy individuality, partly to show off their social status. Cobblers rushed to feed that itch.

This is where the book becomes rich in historical detail. Shawcross knows her stuff. She uses historical documents, paintings, photographs and advertising to show the ongoing development of footwear for both sexes.

It was the advent of modern technologies that made it possible to buy many pairs of shoes. It became easier and cheaper to produce shoes, so they dropped in price. The more inexpensive, the more were bought; the more individualized or richer in materials, the higher the cost, the more coveted by society.

An example? In the 20th century sport shoes developed into sneakers, then into all kinds of designer limited-edition sneakers.

There is also the trend of the shoe as “art.” Some modern designers, such as Thea Cadabra, designed shoes as “wearable art.” Her 1979 dragon shoes of black and white scales and a fish eye with a flaming red ruff is actually usable, even if they look otherwise.

“Shoes” is filled with quirky facts such as the mystery of “concealed shoes,” which are hidden in houses for others to find. Why? Who knows? The meanings behind the trend are still uncertain.

The original Wellingtons were leather boots named for the Duke of Wellington, hero of the war against Napoleon. Now Wellies are better known as rubber boots for keeping your feet dry in rain.

———

©2015 McClatchy Washington Bureau

Visit the McClatchy Washington Bureau at www.mcclatchydc.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC